tl;dr: Historically, heavyweight, slow static analysis tools focused on finding vulnerabilities. This approach is fundamentally not the right path for scaling security in modern development. Security teams today need tools that are fast, customizable to our codebases, can easily be added to any part of the SDLC, and are effective at enforcing secure coding patterns to prevent vulnerabilities

One of my first loves is program analysis. The essential idea is simple: lets write software that can analyze other software to automatically detect (and thus prevent) bugs, or more relevant to me, security vulnerabilities. My first paper ever was on Javascript dynamic analysis to find client-side bugs like XSS, postMessage flaws and so on. It is then a big surprise to a lot of people that when asked what’s my favorite static analysis tool to integrate into CI, I almost always say Semgrep today (and used to say grep for years).

Grep and Semgrep are relatively simple and narrowly scoped. Program analysis researchers have done years of amazing work on smart algorithms to infer invariants of a whole program across function calls; while grep runs a regex on the file and Semgrep runs very complicated and smart regexes on the AST (it does more, but let’s assume that for now).

To understand why I think static analysis as part of an effective SDLC of a modern application often focuses on these simpler tools, let’s walk through a bit of history of the big players in this space and how security engineering needs have evolved. This is, of course, my understanding of this space, but please correct me if I am wrong!

The most famous static analysis tools common for security/reliability are Coverity, Fortify, and the linters/checks that ship with your compiler (GCC, Clang, Visual Studio toolchain). These tools are absolutely amazing! I was an intern at Coverity and I can say that the amount of technical depth and work that goes into creating these tools is mind-boggling. If you have a large C/C++ code, use Coverity! But, two things stand out about these tools:

- Small set of target languages: These tools were really designed for a small set of languages (typically C/C++ and/or Java) and each new language is a lot of work. You have to add support for parsing, then integrate semantics of the new language, and then find & write rules that are relatively high signal.

- Powerful default rules: These tools shipped with a set of rules that were written down by “smart people in an ivory tower” and we had to follow them. The typical static analysis product will not make it easy write your own rules, built on top of the analysis engine. While some tools (notably, Fortify, Checkmarx) do nowadays support writing custom rules, these are not easy to write. The main “product” for these tools were the bugs found, not the analysis engine to build on top of.

This made sense: memory unsafe languages like C/C++ were unique in that they were widely used (and still are), and the patterns for the most common security flaws (memory safety) are relatively well known and stable. The challenge was finding these patterns in a high signal manner, given all the undefined behavior in C/C++’s memory model that is commonly used.

But, modern “DevOps” software development is very different. Two changes in particular are important: surge in number+types of languages and rise of security engineering as a function.

- Surge in languages used

A standard modern app today, even if it wants to have as few languages as it can, will need to have, at the least, an iOS language (Swift/Objective-C), an Android language (Kotlin or Java), an HTML front end language (Javascript, CSS, HTML), a language to manage your cloud infrastructure (Terraform, Pulumi), config files in a bunch of formats (Dockerfile, package.json), and a server side application language (JS via NPM or Python/Ruby or Go if you are lucky). And that’s the minimum: for most realistic scenarios, with large teams and a micro-services architectures, its typical for server-side infrastructure to actually use 5-6 languages if not more, and the mobile platforms to use 4 languages.

Worse, a majority of newer languages are dynamically-typed, interpreted and rely on patterns that are extremely difficult for static analysis. Or, put simply, there are more languages and each language is harder to statically reason about. This means that deep inference based on understanding semantics has struggled to keep up.

For example, Ruby is a 25 year old language but the common use of meta-programming patterns in Ruby makes static analysis extremely difficult (I know cos I once tried!). And new languages take over at a surprising speed: Terraform is a security lynchpin for a large number of SaaS companies, but it was first launched 6 years ago and the community is already talking about newer languages like Pulumi. The classic static analysis approach of spending years working on getting a deep understanding of one language just doesn’t seem to work here. This has led to popularity of tools tied to a specific language and even framework (e.g., brakeman for Rails applications, gosec for Go apps). These tools typically analyze the abstract syntax tree (or, parse tree) of the code and don’t do deeper inter-procedural value/type analysis.

- Rise of Security Engineering

Also called “shift left” or “devsecops”, Security is no longer seen as a checklist step after product/eng work. Instead, effective security goes where the developer goes; making the simplest path fast and safe. The aim is not to find bugs but to prevent vulnerabilities from ever landing in the repo.

To achieve this, engineering and security teams work together on creating frameworks and libraries for safe use, and security teams help provide input and test these frameworks. Secure coding best practices and patterns are defined and enforced. For example, a common pattern is for the security team to define a secure_encrypt function that natively integrates with the key management in use (including key rotation support) and uses strong authenticated encryption algorithms. Secure coding guidelines typically would require security review of an encryption library other than secure_encrypt.

Similarly, when a pentest or bug bounty finds a new vulnerability, security engineering teams use the bugs as an input to a broader review of development best-practices: where else are we using this pattern? Can we quickly find these patterns? What’s the secure way to do this and how do we detect/discourage the unsafe pattern?

As security engineering teams define best practices, they need a scalable, low-noise mechanism to detect unsafe practices and point developers toward safe coding mechanisms. These practices are often specific to the company. A security engineer today will often identify bad patterns, write a safe version, and then rely on the static analysis tool to help identify usage of the unsafe pattern in all old and new code. A static analysis engine that doesn’t allow customization and modification is a non-starter. Working with static analysis tools today is no longer a purely operational workflow, it*’*s a creative venture where a security engineer is building something new on top of the analysis engine.

Creativity and Static Analysis #

What does creativity mean? What does it need? Molly Mielke, in her amazing thesis on computers and creativity, finds that tools that enable creativity with computers have a few characteristics.

Innovation is largely dependent on the human capacity to think creatively, and there is a strong argument to be made that technology’s primary role is to speed up the creative process…. Interoperable, moldable, efficient, and community-driven digital creative tools hold immeasurable potential as co-creators with human beings.

While I encourage you to read her whole thesis to see why this is true, I can personally attest that the tools that have allowed me to do the most have all shared these characteristics (e.g., GitHub). Let’s look at each:

Interoperable tools are ones that don’t limit your work to a single piece of software’s capabilities. Static analysis tools that are only accessible when I login to their interface; that I can’t integrate with all aspects of a developer’s workflow (develop, test, land, push); all severely constrain what security can do with them. While most static analysis tools now have working integrations, they are still severely limited compared to something like grep/Semgrep. Being open-source binaries I can drop anywhere, grep/Semgrep only need the opportunity to run some code and they can be deployed. With closed engines, I have to ask if they support a particular integration; and I typically can’t run them in places where Internet access isn’t available.

Moldable tools allow customization to fit your needs. As I discussed above, modern security teams need to customize tools to their needs, based on the current secure coding practices. Common customizations include file ignore lists (ignore experimental new apps or code in staging only), allowing certain unsafe tools in certain directories. For example, security engineering might want to ban raw SQL, except in the files that implements the ORM itself. But, those files still need to disallow other patterns (e.g.,

eval) so we need to customize one specific rule and not disable the whole engine for these files. This is where Semgrep shines: path ignore lists can be customized to each rule, patterns can depend on other patterns (pattern-not-insideandpattern-insidechecks), and matches can again be filtered (e.g., regex checks on metavariable matches).Molding a tool requires understanding what it is doing. This is again where simplicity of grep/Semgrep wins. When a grep/Semgrep rule has a false positive, it is easy to understand why. In my experience, a typical flow/context/path-sensitive analysis is very frustrating to understand. Is it a false positive or a subtle, true bug? How do you customize something you don’t even understand?

Efficient tools are fast! Writing new rules is iterative. You write a rule that is either too restrictive or too broad, and you iterate until you get it just right. The static analysis engine needs to integrate with the developer’s workflow: a tool that takes hours to run cannot meaningfully integrate with developer workflows either. Grep really wins for this reason; Semgrep is slightly slower but still orders of magnitude faster than the typical tools.

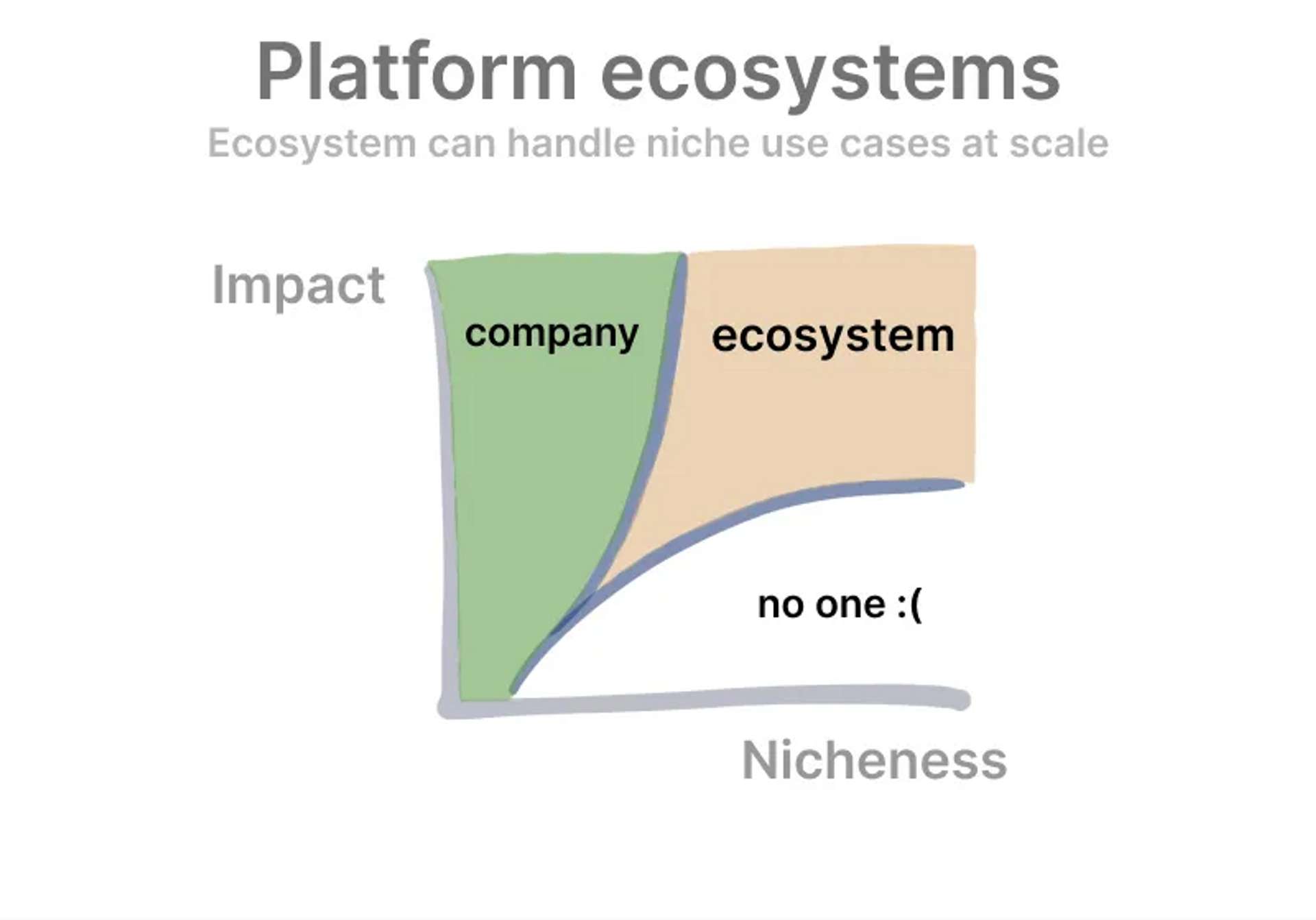

Community-driven: Genius is never alone! True creativity happens when people learn and build upon each other’s work. One of the best things about working in security is the community: all blue/purple teams are in this together and continuously sharing/learning best practices. Historially, static analysis tools have not enabled this community learning/sharing lessons. This is where Semgrep truly wins due to its community! Even if Semgrep doesn’t natively support all languages and frameworks, the community will often have a rule for it. And this repository keeps growing! If a new bug/risky-pattern is found, I can write a rule and everyone using Semgrep immediately benefits from it (and as per above, adapt it to their needs). Kevin created this fantastic image in the context of Canva’s success, but it adapts easily to Semgrep.

Semgrep core can focus on core, wide impact use cases while the community can serve niche needs. And your security team can work on medium impact, highly niche needs of your product. These three options never really existed before.

Conclusion #

Static analysis for security is different today. Software is written with many more dynamic, interpreted language. And modern security teams focus on enforcing secure defaults, not finding bugs.

A static analysis strategy that relies on expensive, heavy integration for each language does not work in this world. Instead, light-weight AST/text-based tools that allow enforcing best practices as defined by the security/engineering teams work best. Moreover, this creative work by security teams needs tools that are interoperable, moldable, efficient, and community driven. I am excited where the Semgrep community goes as it embraces this idea.

Now, this doesn’t mean smarter static analysis tools are dead. The ideas behind these tools are some of the most powerful ideas in computer science. To be successful, the tools built on these ideas need to embrace that they are creative tools in the hands of their users. How can they make their analysis fast, understandable, and community-driven? Github/Semmle has a very similar community-driven approach. But the tool lacks the open interoperability, understandability, and speed of Semgrep. At the same time, Semgrep continues to get smarter with support for constant inference, basic flow analysis and so on.

If Semmle becomes understandable, faster, open; before Semgrep becomes smarter, Semmle could win! But, either way, whatever happens, security teams win! 🙂

Thanks to Clint Gibler, Matthew Finifter, Max Burkhardt, Sean Byrne for their feedback. All mistakes are mine and I would love your feedback.

---🙏🙏🙏

Since you've made it this far, sharing this article on your favorite social media network would be highly appreciated 💖! For feedback, please ping me on Twitter.

Published